The UK’s Economic Decline Since 2008: A Comprehensive Analysis of Policy Failures and Missed Opportunities

The United Kingdom faces an unprecedented economic challenge. Since the 2008 financial crisis, a series of compounding policy failures, missed opportunities, and external shocks have left Britain significantly poorer than it should have been, trailing behind its international competitors across virtually every major economic metric. The evidence is stark: GDP per capita is nearly £11,000 lower than it would have been if pre-crisis trends had continued, productivity has stagnated for over a decade, and the UK now ranks last among G7 nations for business investment.

This economic malaise is not the result of a single catastrophic event, but rather the cumulative effect of multiple policy missteps and external shocks that British governments have failed to adequately address. The failure to capitalise on historically low interest rates post-2008, the self-inflicted wound of Brexit, the inadequate response to COVID-19, and the substantial financial commitment to supporting Ukraine have all contributed to Britain’s relative economic decline. Perhaps most damning of all, the current Labour government appears either unaware of the scale of the challenge or unwilling to take the bold action required to reverse this trajectory.

UK GDP per capita growth has significantly lagged behind other G7 economies since 2008

The 2008 Financial Crisis: Where Britain’s Troubles Began

The 2008 financial crisis hit the United Kingdom harder than virtually any other developed economy, and the reasons why reveal fundamental structural weaknesses that persist to this day. Britain’s economy had become dangerously over-financialised during the New Labour years, with the combined balance sheets of UK clearing banks reaching a staggering 450% of GDP by 2010, compared to just 75% in 1990. This unprecedented expansion of the financial sector made Britain uniquely vulnerable when the global financial system collapsed.

The scale of the UK’s exposure was extraordinary. By mid-2009, HM Treasury held a 70.33% controlling shareholding in the Royal Bank of Scotland Group and a 43% shareholding in Lloyds Banking Group. The banking sector’s collapse necessitated the most extensive state intervention in British economic history since World War II, with the government effectively nationalising large swathes of the financial system.

However, it was not just the severity of the initial shock that damaged Britain’s long-term prospects, but the policy response that followed. While other countries used a mix of spending cuts and tax increases to address post-crisis fiscal imbalances, the UK pursued an exceptionally aggressive austerity programme that would prove economically and socially devastating. Between 2010 and 2019, the UK implemented spending cuts equivalent to £540 billion in lost public expenditure – a figure that dwarfs the cost of any other policy initiative in modern British history.

The economic logic behind austerity was fundamentally flawed from the outset. The Cameron-Osborne government’s belief in “expansionary fiscal contraction” – the idea that cutting government spending would boost business confidence and private investment – proved to be entirely wrong. Instead of crowding in private investment, austerity undermined economic demand, weakened worker bargaining power, and contributed to the longest period of wage stagnation since the Victorian era.

The Historic Missed Opportunity: Ultra-Low Interest Rates and the Failure to Invest

Perhaps the most economically damaging decision of the post-2008 period was the failure to take advantage of historically low interest rates to fund a major public investment programme. From 2009 to 2022, the UK government could borrow at rates close to zero in real terms, and at times at negative real rates when adjusted for inflation. This represented a once-in-a-generation opportunity to invest in the infrastructure, housing, and productive capacity that Britain desperately needed.

The Bank of England’s base rate remained at 0.5% for seven years from 2009 to 2016, before falling even further to 0.25%. During this period, inflation often exceeded these nominal rates, meaning the government was effectively being paid to borrow money. Yet instead of seizing this opportunity, successive governments imposed spending cuts and allowed public investment to fall to historically low levels.

Research from the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose demonstrated that quantitative easing was largely ineffective at stimulating business investment because there was insufficient demand in the economy for loans. The study found that neither low interest rates nor corporate bond purchases increased firms’ demand for investment. Instead, investments are stimulated by expectations about future opportunities, which are positively influenced by aggregate demand and strategic government investments.

The opportunity cost of this policy failure is enormous. Conservative estimates suggest that the UK missed out on at least £200 billion worth of productive investment during this period. Had Britain followed the example of countries like Germany, which maintained higher levels of public investment even during periods of fiscal consolidation, the UK’s productivity performance and long-term growth prospects would be markedly better today.

UK has the lowest business investment rates among G7 countries in 2022

Brexit: The Self-Inflicted Economic Wound

Brexit represents perhaps the most significant act of economic self-harm by any major economy in the post-war period. Nine years after the referendum, the economic damage is no longer a matter of speculation but measurable fact. The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that Brexit has reduced UK productivity by 4%, lowering GDP by approximately £40 billion annually compared to remaining in the European Union.

The investment impact of Brexit has been particularly severe. Business investment growth in the UK has been anaemic since the referendum, with the country falling to last place among G7 nations for business investment as a share of GDP. Between the referendum and 2019, UK business investment grew by less than 2%, compared to over 6% in every other G7 economy. The Bank of England’s analysis suggests that nominal business investment growth has been 3-4 percentage points weaker than it otherwise would have been specifically as a result of Brexit uncertainty and the expected impact on future sales.

The trade impacts have been equally dramatic. Research using the National Institute Global Econometric Model suggests that increased non-tariff trade barriers resulting from Brexit have led to a 23.7% decrease in imports from the EU and an 18.6% decrease in exports to the EU. These figures align closely with official data showing UK trade with the EU falling significantly since the end of the transition period.

Perhaps most concerning is the long-term productivity impact. Brexit has reduced the UK’s access to EU single market benefits including technology transfer, skilled migration, and competitive pressures that drive innovation. The London School of Economics research suggests these effects will compound over time, with the productivity gap between the UK and EU countries widening in the years ahead.

The fiscal impact has been equally severe. John Springford’s analysis suggests that Brexit cost the UK exchequer approximately £40 billion in lost tax revenues between 2019 and 2024 – money that could have been used to avoid the tax rises imposed by successive governments. This represents a “Brexit tax” on British households that will persist for years to come.

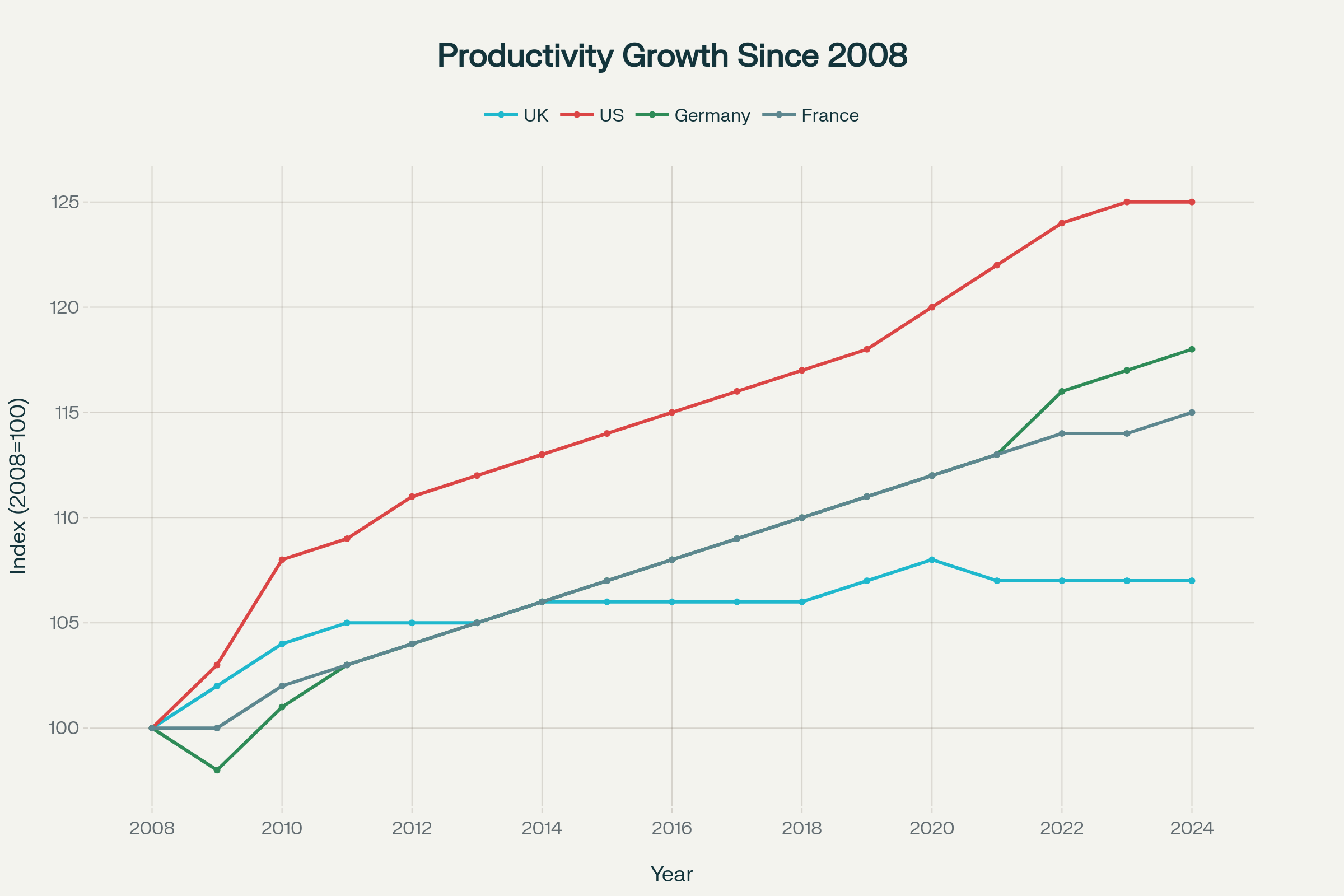

UK productivity has stagnated since 2008 while other major economies recovered more strongly

COVID-19: A Crisis That Exposed Britain’s Weaknesses

The COVID-19 pandemic struck the UK economy with unprecedented force, causing GDP to fall by nearly 10% in 2020 – the largest annual contraction in over 300 years. While the pandemic affected all countries, international comparisons reveal that the UK suffered more severely than most of its peers and has recovered more slowly.

Several factors explain why the UK was particularly vulnerable to the pandemic’s economic impact. First, the UK economy has a higher proportion of “social consumption” activities – restaurants, hotels, entertainment, and retail – that were most affected by lockdown restrictions. Second, the UK experienced longer and more stringent lockdowns than many other countries, partly due to higher infection rates and a slower initial policy response.

However, the UK’s poor performance during COVID-19 was not simply a matter of bad luck. Years of austerity had weakened the country’s resilience and ability to respond effectively to the crisis. Public health capacity had been eroded through years of spending cuts, contributing to the need for longer and more severe lockdowns. The UK entered the pandemic with one of the weakest public health systems in the OECD relative to the size of its economy.

The fiscal response, while necessary, was also more costly and less effective than in many peer countries. The UK spent approximately £106 billion over the first two years of the pandemic on direct support measures and economic consequences. This figure does not include the broader economic costs of the UK’s longer lockdowns and slower recovery.

Most concerning, the UK’s recovery from COVID-19 has been slower than most comparable countries. While UK GDP growth outpaced other G7 economies in the first quarter of 2025, growing by 0.7%, this followed an extended period of underperformance. The UK’s cumulative economic recovery since the start of the pandemic remains weaker than the United States, Canada, and most European economies.

The Ukraine War: Costly Solidarity with Long-term Consequences

Britain’s support for Ukraine represents a significant financial commitment that, while morally justified, has substantial economic implications that the government has largely failed to acknowledge or plan for. The UK has committed £21.8 billion to Ukraine, including £13 billion in military support and £8.8 billion in non-military assistance. This represents one of the largest peacetime military expenditures in British history.

The direct costs are substantial enough, but the indirect economic impacts have been far greater. Analysis suggests that the combined direct and indirect costs to Britain over the first two years of the war totalled approximately £106 billion, equivalent to £53 billion annually. This includes direct aid, the cost of supporting Ukrainian refugees, higher energy prices, and broader economic disruption.

Energy costs have been particularly significant. Britain’s heavy reliance on natural gas for electricity generation and heating made it uniquely vulnerable to the energy price spike following Russia’s invasion. The Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit estimates that Britain spent £60-70 billion on wholesale gas markets in the twelve months after February 2022, adding £50-60 billion in additional costs compared to pre-war levels.

The government’s response, including the Energy Price Guarantee and various support schemes, helped shield households from the worst impacts but at enormous fiscal cost. These emergency interventions contributed to the sharp increase in government borrowing and ultimately to the tax rises imposed by successive chancellors.

Looking ahead, the UK’s commitment to provide £3 billion annually in military aid to Ukraine until 2030-31 represents a permanent addition to Britain’s defence spending obligations. While this commitment enjoys broad public support, it effectively reduces the fiscal space available for domestic priorities including health, education, and infrastructure investment.

Austerity’s Devastating Legacy: The Human and Economic Cost

The austerity programme imposed between 2010 and 2019 represents one of the most economically destructive policy decisions in modern British history. Far from achieving its stated goals of restoring economic confidence and reducing the deficit more quickly, austerity prolonged economic weakness and inflicted severe social costs that persist to this day.

The scale of spending cuts was unprecedented in peacetime. Public service spending was cut by approximately 4% in real terms between 2010 and 2019, even as the economy and population grew. This represented a complete reversal of the normal relationship between economic growth and public spending, creating a prolonged period of fiscal contraction that undermined economic recovery.

The human cost has been severe. Research by LSE and King’s College London found that austerity spending cuts cost the average person in the UK nearly half a year in life expectancy between 2010 and 2019, equivalent to about 190,000 excess deaths. The research identified several mechanisms through which austerity increased mortality, including cuts to welfare that led to increased “deaths of despair” and deteriorating ambulance response times due to healthcare spending constraints.

The economic cost has been equally devastating. The Progressive Economics Forum calculates that austerity cost Britain £540 billion in lost public expenditure over the 2010-19 period. This represents resources that could have been invested in infrastructure, education, healthcare, and other productivity-enhancing activities. Instead, the UK emerged from the austerity period with crumbling public services, deteriorating infrastructure, and a less skilled workforce.

Perhaps most damaging of all, austerity undermined the UK’s long-term growth potential. By cutting investment in education, infrastructure, and research, the government reduced the economy’s productive capacity for years to come. The UK’s poor productivity performance since 2010 can be directly traced to these policy choices, with consequences that will persist for decades.

The Productivity Puzzle: Why Britain Can’t Compete

Britain’s productivity performance since 2008 has been historically unprecedented in its weakness. Before the financial crisis, UK productivity grew at around 2% annually, roughly in line with other advanced economies. Since 2008, productivity growth has averaged just 0.5% per year, meaning that output per worker is now 24% lower than it would have been if pre-crisis trends had continued.

This productivity stagnation is not merely a statistical curiosity – it represents the fundamental reason why British workers’ living standards have stagnated for over a decade. As economist Paul Krugman observed, “productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything”. Without productivity growth, it is impossible to sustain rising wages and improving living standards.

International comparisons reveal the scale of Britain’s productivity problem. In 2022, US workers produced 28% more value per hour than their UK counterparts, while French and German workers were 13-14% more productive. These gaps have widened since the financial crisis, as other countries recovered more successfully from the global downturn.

Several factors explain Britain’s productivity malaise. First, the UK has chronically underinvested in the physical capital that makes workers more productive. Business investment as a share of GDP has been lower in the UK than any other G7 country for three consecutive years, and the UK has had the lowest investment rate in the G7 for 24 of the last 30 years.

Second, the UK’s financial system has proved unable to channel capital efficiently to productive uses. The financial sector’s focus on short-term returns and dividends, rather than long-term investment, has created an environment unconducive to productivity-enhancing investment. Access to finance for investment is more difficult and more costly in the UK than in many comparable countries.

Third, Britain’s infrastructure deficits have become increasingly severe constraints on productivity growth. Poor transport links, inadequate energy infrastructure, and slow rollout of digital technologies all limit the productive potential of British businesses and workers. The failure to invest adequately in infrastructure during the period of ultra-low interest rates represents a historic missed opportunity.

Investment Failure: The Root of Britain’s Economic Problems

The UK’s investment performance represents perhaps the most fundamental cause of its economic underperformance since 2008. Business investment in the UK is not only the lowest in the G7 but ranks 28th out of 31 OECD countries. Countries like Slovenia, Latvia, and Hungary all attract higher levels of private sector investment than the UK as a percentage of GDP.

The investment deficit is not a recent phenomenon but reflects a long-term structural problem. The UK has had the lowest level of investment in the G7 for 24 of the last 30 years. The last time the UK was at the G7 median for investment was in 1990. IPPR analysis suggests that if the UK had maintained average G7 investment levels over the past three decades, there would have been an additional £1.9 trillion worth of investment – roughly equivalent to an entire year’s GDP.

The investment gap affects all categories of capital formation. Private sector investment, manufacturing investment, and investment in plant and equipment have all underperformed relative to international peers. This broad-based weakness suggests systemic problems with the UK’s investment environment rather than issues in specific sectors.

Brexit has significantly worsened the UK’s investment performance. The uncertainty created by the referendum and subsequent negotiations caused business investment growth to stagnate from 2016 onwards. Even after Brexit was “done,” the new trading arrangements and regulatory uncertainties continue to deter long-term business investment in the UK.

The consequences of chronic underinvestment compound over time. Each year of weak investment means fewer productive assets for workers to use, slower adoption of new technologies, and reduced competitiveness in international markets. This creates a vicious cycle where weak investment leads to poor productivity performance, which in turn discourages further investment.

Current Government Response: Too Little, Too Late?

The Labour government elected in July 2024 has acknowledged the scale of Britain’s economic challenges and has committed to achieving “the highest sustained growth in the G7”. However, the policies announced so far appear insufficient to address the magnitude of the problems the country faces, and the government’s fiscal constraints may prevent it from taking the bold action required.

Labour’s growth strategy rests on seven pillars: economic stability, investment and infrastructure, regional development, skills and employment, industrial strategy, innovation, and trade. While these are sensible priorities, the scale of proposed interventions appears modest relative to the size of the challenges. The National Wealth Fund, capitalised at £7.3 billion over the entire parliamentary term, represents a fraction of the investment deficit that needs to be addressed.

Most concerning, the government has committed to fiscal rules that may prevent it from making the large-scale public investments needed to kickstart economic recovery. Labour has pledged that “the current budget must move into balance, so that day-to-day costs are met by revenues and debt must be falling as a share of the economy by the fifth year of the forecast”. These constraints, combined with promises not to raise major taxes, create what the Institute for Fiscal Studies has described as a “trilemma” – the government will have to choose between raising taxes, cutting spending, or relaxing its fiscal rules.

The government’s approach to growth also fails to acknowledge the international dimension of Britain’s economic challenges. While Labour talks about partnering with business and investing in key sectors, there is little recognition that the UK is competing for mobile international capital with countries that offer more attractive investment environments. Without addressing the fundamental structural problems that deter investment – including regulatory uncertainty, skills shortages, and infrastructure deficits – it is unclear how the government’s modest interventions will achieve the ambitious growth targets it has set.

Perhaps most troubling, there is little evidence that the government fully grasps the scale of the economic hole that Britain has dug itself into. The cumulative impact of austerity, Brexit, COVID-19, and chronic underinvestment has left the UK’s economy fundamentally weakened compared to international competitors. Modest policy adjustments will not be sufficient to address problems of this magnitude.

International Comparisons: How Far Britain Has Fallen

The scale of Britain’s relative economic decline becomes clear when comparing its performance with international peers across multiple metrics. On virtually every measure of economic performance – growth, productivity, investment, and competitiveness – the UK has fallen behind countries it once matched or exceeded.

The GDP comparison is particularly stark. While the UK economy grew modestly in the first quarter of 2025, outpacing other G7 countries, this masks a longer-term pattern of underperformance. Since 2008, UK GDP per capita has grown more slowly than the US, EU27, and Germany, despite starting the period with similar productivity levels.

The investment gap is even more concerning. The UK’s business investment rate of approximately 10% of GDP compares unfavourably with rates of 12-14% in other G7 countries. This represents not just a current disadvantage but a growing competitive deficit as other countries build more modern, productive economies while Britain falls behind.

Productivity comparisons reveal the cumulative impact of these investment deficits. US productivity has grown by approximately 25% since 2008, while UK productivity has increased by only 7%. This growing gap means that American workers can command higher wages because they produce more value per hour worked. Similar patterns are evident when comparing the UK with Germany and France.

The UK’s decline in international competitiveness rankings tells a similar story. Once regarded as one of the most business-friendly environments in the world, Britain now struggles to attract the mobile international investment that drives modern economic growth. Brexit has made this problem worse by creating additional barriers to trade and investment with the UK’s largest trading partners.

The Cost of Policy Failures: A £1.8 Trillion Reckoning

The cumulative cost of Britain’s policy failures since 2008 is staggering in scale. Conservative estimates suggest that the combination of austerity, Brexit, missed investment opportunities, and crisis responses has cost the UK economy at least £1.8 trillion over the past decade and a half.

uk_economic_costs_analysis.csv

Generated File

The austerity programme alone accounts for £540 billion in lost public expenditure, representing resources that could have been invested in productivity-enhancing infrastructure, education, and research. Brexit is estimated to cost £40 billion annually in lost GDP, with cumulative costs likely to exceed £300 billion by the end of this decade. The failure to take advantage of ultra-low interest rates to fund public investment represents a missed opportunity worth at least £200 billion.

The investment gap with other G7 countries totals £563 billion over the 2006-2021 period, representing capital that could have made British workers more productive and competitive. The productivity gap with pre-2008 trends suggests lost economic potential worth hundreds of billions more.

These figures represent more than accounting entries – they translate directly into lower living standards for British families. GDP per capita is nearly £11,000 lower than it would have been if pre-crisis trends had continued. Real wages remain below 2008 levels across much of the UK, and if pay had kept pace with pre-crisis trends, the average UK worker would be earning over £10,000 more per year.

Systemic Problems: Why Quick Fixes Won’t Work

Britain’s economic problems are not simply the result of individual policy mistakes but reflect deeper systemic issues that will require fundamental reforms to address. The UK’s economic model, developed during the Thatcher era and refined under New Labour, has proved unsuited to the challenges of the 21st century global economy.

The over-reliance on financial services, while profitable during the boom years, created dangerous vulnerabilities that were exposed in 2008 and have not been adequately addressed. The financial sector’s focus on short-term profits rather than long-term productive investment continues to starve the rest of the economy of the capital it needs to grow and modernise.

The UK’s approach to fiscal policy has been similarly dysfunctional. The obsession with deficit reduction during periods of economic weakness has proved economically self-defeating, prolonging downturns and undermining the public investment needed for long-term growth. The failure to distinguish between current spending and capital investment has led to chronic underinvestment in the infrastructure and skills that modern economies require.

Perhaps most fundamentally, Britain has failed to develop effective institutions for economic governance. Unlike countries such as Germany, which maintained a focus on manufacturing and long-term investment even during the financial boom years, the UK allowed short-term financial considerations to dominate economic policy-making. The result has been a series of boom-bust cycles that have left the economy weaker after each downturn.

The planning system, while important, is not the primary constraint on British economic growth that many politicians claim. The evidence suggests that macroeconomic factors – particularly the failure to maintain adequate levels of investment and the uncertainty created by policy instability – are far more significant barriers to growth than planning regulations.

The Path Not Taken: What Britain Could Have Achieved

To understand the scale of the opportunity cost of Britain’s policy failures, it is worth considering what the UK economy could have achieved if different choices had been made. The counterfactual is not simply academic – it represents the living standards that British families have been denied through poor economic management.

If the UK had maintained pre-2008 productivity trends, GDP per capita would be approximately 24% higher than current levels. For a median household, this would translate into thousands of pounds of additional income each year. The economy would be large enough to support better public services without requiring higher tax rates, and Britain would be in a much stronger position to face future challenges.

Had the government used the period of ultra-low interest rates to fund a major infrastructure investment programme, Britain could have developed world-class transport networks, energy systems, and digital infrastructure. This would have created jobs during the recession, improved productivity in the long term, and left the country better prepared for challenges like climate change and technological disruption.

If Brexit had been avoided, or if a much softer form of Brexit had been negotiated, Britain would have retained access to the world’s largest single market while maintaining the productivity benefits of European integration. Investment levels would likely be higher, trade would be flowing more freely, and the UK would be better placed to attract mobile international capital.

The tragedy is that none of these outcomes required impossible policy choices or unprecedented interventions. Countries like Germany, Denmark, and South Korea have successfully pursued long-term investment strategies that have delivered higher productivity and living standards for their citizens. Britain had the resources and capabilities to follow similar paths but chose not to do so.

Conclusion: The Urgent Need for Recognition and Action

The evidence is overwhelming: the United Kingdom has suffered an unprecedented economic decline since 2008, falling behind international competitors across virtually every measure of economic performance. This decline is not the result of inevitable global trends or unavoidable external shocks, but the direct consequence of policy choices made by successive British governments.

The failure to invest during the period of ultra-low interest rates, the self-inflicted wound of Brexit, the economically destructive austerity programme, and the chronic underinvestment in productive capacity have combined to leave Britain significantly poorer than it should have been. The human cost of these failures – measured in lost income, reduced life expectancy, and diminished opportunities – is immense and continues to grow.

Most concerning of all, there is little evidence that the current government fully understands the scale of the challenge or is prepared to take the bold action necessary to reverse Britain’s decline. The modest policies announced so far, while positive in direction, are insufficient in scale to address problems that have been more than a decade in the making.

Time is running out for Britain to reverse its economic decline before it becomes entrenched. Other countries are not standing still – they are continuing to invest in their productive capacity, develop new technologies, and build more competitive economies. Each year that Britain fails to match their efforts is another year of relative decline that will be harder to reverse.

The UK needs to acknowledge that it faces an economic emergency that requires emergency measures. This means abandoning failed fiscal orthodoxies, making large-scale public investments in infrastructure and skills, and developing a long-term industrial strategy that can compete with the best in the world. Without such recognition and action, Britain risks becoming a permanently second-tier economy – a fate that would have been unthinkable just two decades ago but now appears increasingly likely unless dramatic action is taken immediately.