When Britannia No Longer Rules the Waves: The Royal Navy’s Current Crisis

The phrase “Britannia rules the waves” once struck fear into the hearts of enemies and pride into the souls of Britons. Today, it might be more accurate to say “Britannia occasionally visits the waves, when the ships aren’t broken down.” The Royal Navy, once the undisputed master of the world’s oceans, now finds itself in what can only be described as a state of crisis—stretched thin, underequipped, and struggling to maintain even basic operational capabilities.

Aerial view of HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier with multiple aircraft on deck in the open sea.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

The stark reality of the Royal Navy’s decline becomes immediately apparent when examining the numbers. The current condition of the RN is alarming, with almost every aspect of its capabilities understrength or overstretched. By the end of 2025, the Royal Navy will operate with just seven frigates—a figure that would have been unthinkable during the height of British naval power.

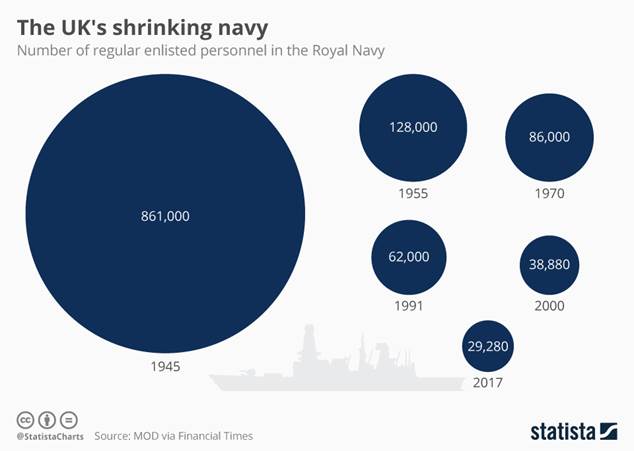

A graph showing the decline in the number of regular enlisted personnel in the UK’s Royal Navy from 1945 to 2017.

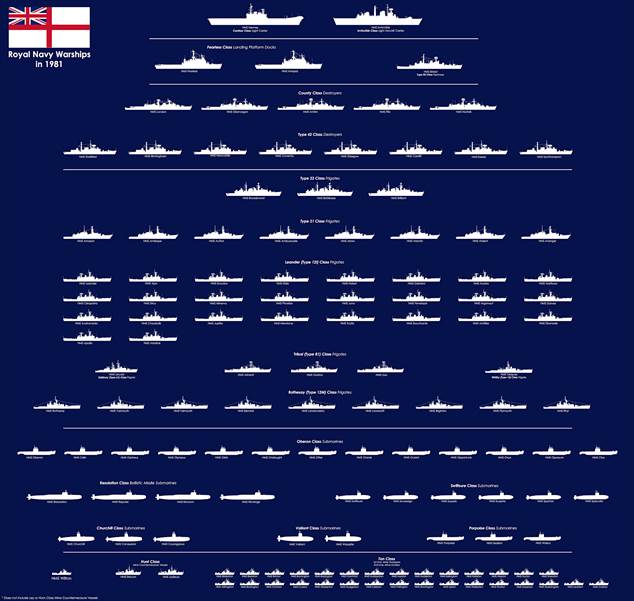

To put this in perspective, the Royal Navy that fought in the Falklands War in 1982 deployed more frigates to that single conflict than the entire service can now muster globally. The service has been reduced from a force capable of simultaneous worldwide operations to what critics accurately describe as a “part-time blue water navy”—capable of generating an occasional carrier strike group but lacking the sustained logistics and support vessels for prolonged distant operations.

Silhouettes and names of Royal Navy warships by class from 1981 illustrating the fleet’s composition.

The Procurement Nightmare

The Ministry of Defence’s procurement system has become a byword for delay, cost overruns, and strategic confusion. The National Audit Office has consistently described the MoD’s equipment plans as “unaffordable,” with the Royal Navy facing the largest funding shortfall of the three services at £4.3 billion over the 2020 to 2030 period. By December 2023, this situation had worsened dramatically, with the defence plan described as £16.9 billion over budget, and Royal Navy costs alone rising by £16.4 billion (or 41%).

This isn’t just about money—it’s about capability gaps that leave Britain vulnerable. The Type 26 frigates, desperately needed to replace aging Type 23s, won’t achieve full operational capability until well into the 2030s. Meanwhile, the five Type 31 “general purpose” frigates being built have no anti-submarine warfare capability at all—a glaring omission when the primary threat to UK maritime security comes from Russian submarines.

Royal Navy Type 26 frigate HMS Cardiff under construction with scaffolding and protective wraps in shipyard.

Power Projection: More Projection Than Power

The Royal Navy’s two aircraft carriers, HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales, represent both the service’s greatest achievement and its most telling weakness. These £3.2 billion vessels can indeed project British power globally, as demonstrated by Carrier Strike Group 2025’s current deployment. However, they also highlight the service’s fundamental problem: too big and expensive to fail, yet lacking adequate support.

The Royal Navy’s aircraft carrier HMS Prince of Wales sailing near a coastal mountain range.

The carriers were designed for expeditionary warfare based on strategic thinking from the 1990s, but the supporting infrastructure for sustained power projection has been systematically dismantled. The Navy’s Albion-class assault ships were withdrawn from service in 2024/25, significantly impacting the UK’s power projection capabilities. The Royal Fleet Auxiliary, crucial for sustaining operations at distance, has been reduced to a shadow of its former self, with only one Fleet Solid Support ship remaining operational.

The Manpower Crisis

Ships are only as effective as the sailors who crew them, and here too the Royal Navy faces severe challenges. Recruitment shortfalls and retention problems have left the service struggling to fully crew its existing vessels, let alone the new ships planned for the future. The problem is so acute that some vessels remain alongside not due to mechanical issues but simply because there aren’t enough qualified personnel to take them to sea safely.

A Legacy of Cuts

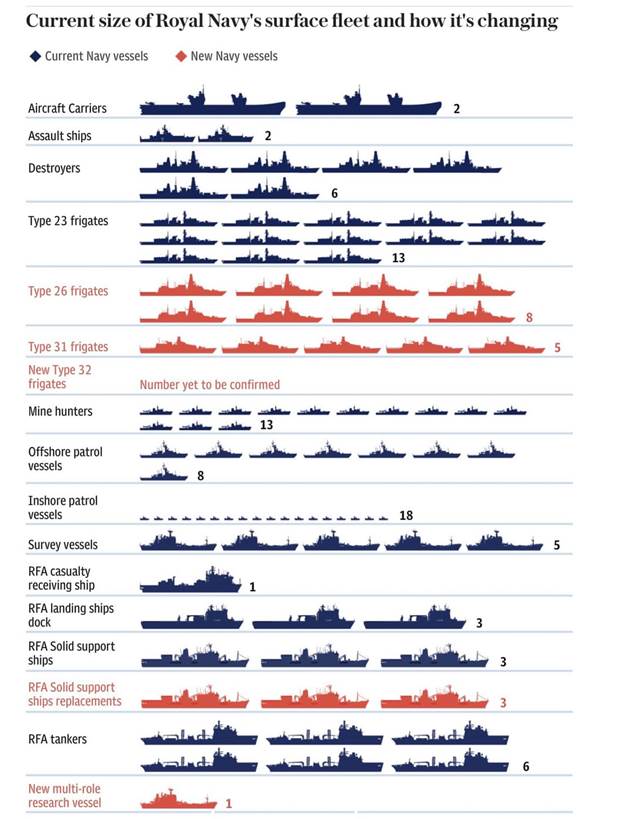

The contrast between past and present is stark when examining the Royal Navy’s current surface fleet composition. Where once Britain maintained dozens of destroyers and frigates, today’s fleet struggles with basic coverage requirements.

Infographic displaying the current and incoming size of the Royal Navy’s surface fleet by vessel type.

The End of an Era

The decommissioning of aging vessels without adequate replacement highlights the service’s predicament. Type 23 frigates, the backbone of the fleet for decades, are being retired faster than their replacements can be built and commissioned.

The decommissioned Royal Navy Type 23 frigate ex-HMS Montrose anchored and awaiting disposal in calm waters.

A Glimmer of Hope? The 2025 Strategic Defence Review

The newly elected Labour government’s Strategic Defence Review, published in June 2025, attempts to address some of these challenges through the creation of a “New Hybrid Navy”. The plan promises increased submarine capabilities, with fleet submarine numbers potentially rising to 12 boats starting in the latter 2030s, and the development of Multi-Role Strike Ships (MRSS) to replace the scrapped amphibious vessels.

The government has committed to increasing defence spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2027 and 3.5% by 2035, which sounds impressive until you realize that much of this increase will be “swallowed by the MoD’s bloated procurement programs that are typically delayed and always over budget”.

The Reality Check

The most honest assessment comes from naval analysts who describe the modern Royal Navy as having been “reduced to a small regional naval power, able occasionally to deploy limited forces”. This isn’t the criticism of armchair admirals but the measured assessment of defence professionals watching a once-great institution struggle with impossible demands and inadequate resources.

The service can still mount impressive displays of capability—Carrier Strike Group 2025’s global deployment demonstrates this. But sustainability is the problem. The RN can generate an occasional CSG at distance from time to time and keep a warship or two forward deployed, but its support assets are now too limited to conduct operations at distance on a sustained basis.

Missing the Point on Modern Threats

Perhaps most troubling is the mismatch between the threats Britain actually faces and the capabilities the Royal Navy is building. In the 1980s, the service correctly focused on anti-submarine warfare to counter the Soviet submarine threat. Today, with Russia once again the primary maritime threat, the RN’s ASW fleet is pitifully weak, with modern platforms years away from full operational capability.

Instead of building the submarines and ASW frigates needed to defend British waters and NATO’s Atlantic lifelines, precious resources are being spent on general-purpose frigates “intended to be forward deployed to replace OPVs,” with unclear additional capability and no ASW capacity.

The Verdict

The Royal Navy remains a professional, well-trained force with pockets of genuine capability. Its nuclear submarine force maintains credible deterrence, its personnel are among the world’s best, and it can still mount limited but impressive operations when required. However, as a force capable of defending British interests and projecting sustained power overseas, it has been hollowed out by decades of cuts, procurement failures, and strategic confusion.

The service that once policed the world’s oceans now struggles to maintain basic presence in home waters while simultaneously meeting NATO commitments and protecting British interests globally. Unless the 2025 Strategic Defence Review’s promises translate into actual, deliverable capabilities—and quickly—Britain risks finding itself a maritime nation without effective maritime power.

For a country that depends on seaborne trade for its very survival, this isn’t just a military issue—it’s a national security crisis that demands urgent, sustained attention. The question isn’t whether Britain can afford to properly fund its Navy; it’s whether Britain can afford not to.

The evidence is clear, even if the political will to act upon it remains questionable. As any good copper will tell you, ignoring a problem doesn’t make it go away—it just makes it worse.