London’s Economic and Political Dominance: The Architects of Britain’s Capital-Centric State

London’s contemporary status as the overwhelmingly dominant economic and political center of the United Kingdom represents one of the most remarkable concentrations of power in any developed democracy. With 21.9% of the UK’s total economic output and serving as home to Westminster and Whitehall, London’s dominance extends far beyond what would be expected of a mere capital city. This extraordinary concentration of power did not emerge organically but was deliberately constructed through a series of calculated policy decisions, institutional arrangements, and strategic choices made by key political figures across centuries, with particularly dramatic acceleration from the 1980s onward.

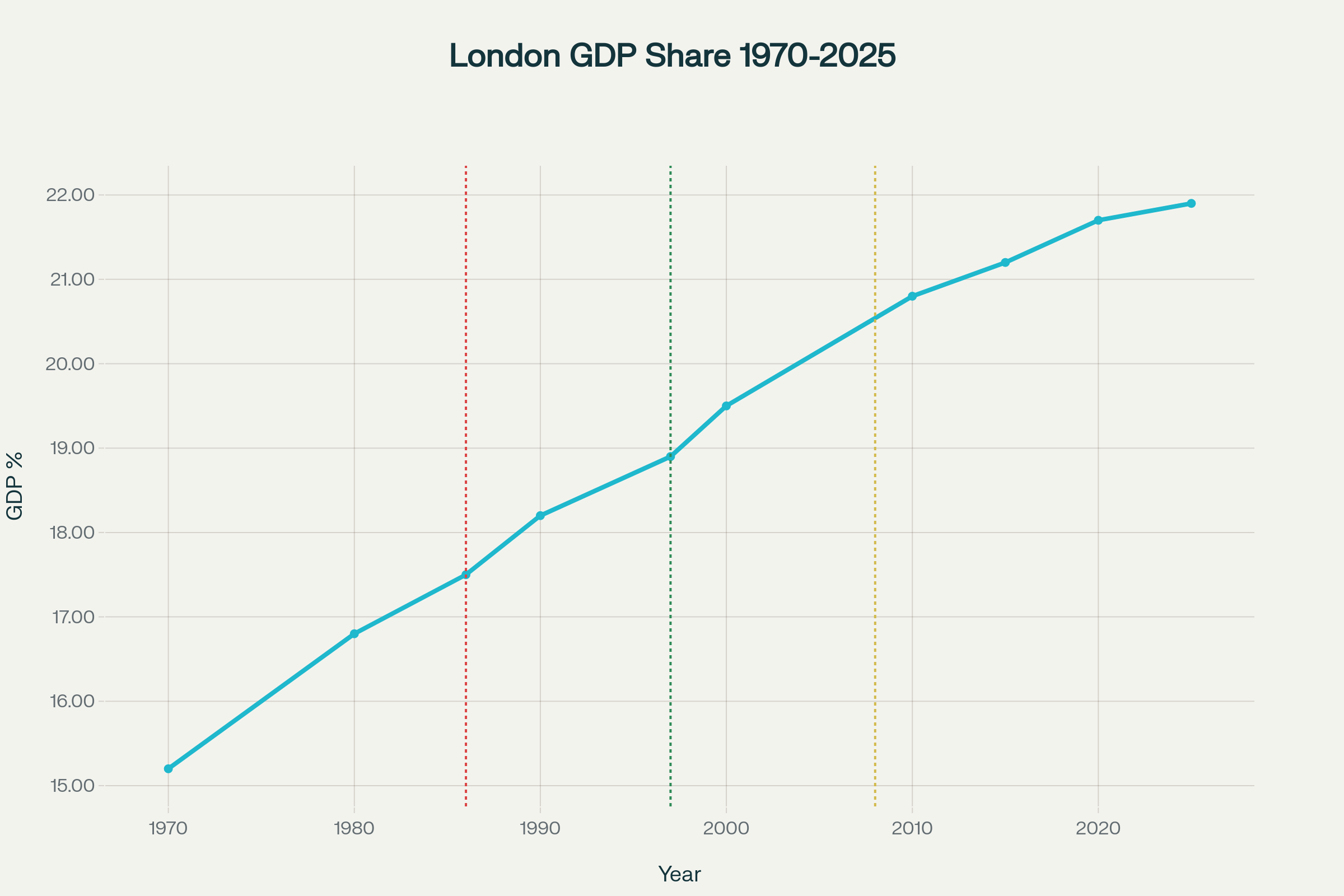

London’s Share of UK Economic Output (1970-2025): The steady rise of the capital’s economic dominance, accelerating after key policy decisions

The data reveals a stark reality: London’s share of UK economic output has grown relentlessly from 15.2% in 1970 to its current historic high of 21.9%. This represents a level of economic concentration greater than at any point in British history, even exceeding the capital’s dominance during the height of the British Empire. The implications are profound—London now finances approximately 20% of the rest of the UK’s total GDP, making the country uniquely dependent on a single metropolitan region.

The Medieval Foundations: William the Conqueror and Ancient Privileges

London’s path to dominance began with deliberate political decisions in the medieval period. When William the Conqueror granted the first recorded royal charter to the City of London around 1067, he established a framework of privileges and self-governance that would prove foundational. Unlike other English cities, the City of London was granted the right to “enjoy its ancient liberties” as confirmed in Magna Carta, creating a unique legal status that persists today.

This medieval foundation established the City of London Corporation as what one analysis describes as “incorporated by prescription”—a legal entity whose authority is so ancient that the law presumes its legitimacy. The Corporation’s unique powers include exemption from the Freedom of Information Act and Human Rights Act, its own police force, and crucially, its own courts including the Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey). These privileges created an institutional framework that would later enable the City to operate with unprecedented autonomy in financial matters.

The significance of these early arrangements cannot be overstated. As one expert noted, the City of London’s “continuous legal existence over many centuries” and its “power to alter its own constitution” made it fundamentally different from other British local authorities. This institutional autonomy would prove crucial when London later emerged as a global financial center.

The Bank of England: Engineering Financial Supremacy

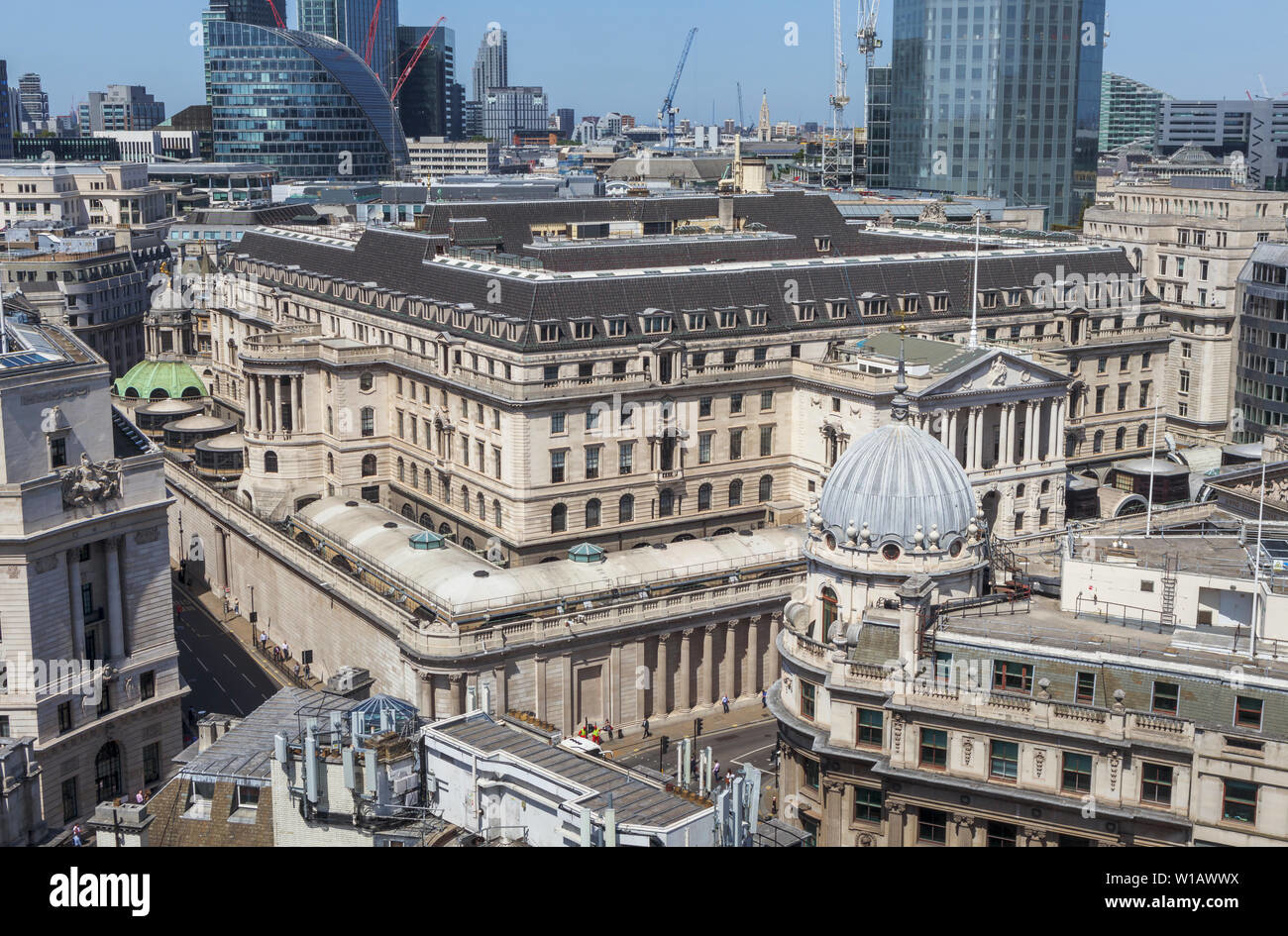

The establishment of the Bank of England in 1694 marked the beginning of London’s systematic transformation into a global financial hub. Unlike other European financial centers, the Bank of England was designed from its inception to serve both private commercial interests and state financing needs. As research demonstrates, the Bank “extended large amounts of credit to support the British private economy and to support an increasingly centralized British state”.

Aerial view of the Bank of England building and surrounding financial district in the City of London, highlighting the classical architecture amidst ongoing urban development

The Bank’s role expanded dramatically during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Bank Charter Act of 1844 granted it exclusive rights to issue banknotes in England and Wales, consolidating monetary control in London. By the mid-19th century, London had established itself as what Walter Bagehot called “the sole great settling-house of exchange transactions in Europe”. This dominance was achieved through deliberate policy choices that concentrated financial authority in the capital.

Research reveals that “by 1913 about 50% of capital investment throughout the world had been raised in London, making Britain the largest exporter of capital by a wide margin”. This extraordinary concentration of global financial flows in London was not accidental but the result of institutional design and policy decisions that favored the capital over regional alternatives.

The Thatcher Revolution: Big Bang and Systematic Deregulation

The most dramatic acceleration of London’s dominance occurred during Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, particularly through the “Big Bang” deregulation of October 27, 1986. This represented a conscious decision to prioritize London’s global competitiveness over broader national economic balance. As Chancellor Nigel Lawson orchestrated these changes, he explicitly aimed to transform London into “a major world financial centre”.

The Big Bang’s four key components systematically removed constraints on London’s financial sector: abolishing fixed commission rates, eliminating the separation between stockbrokers and jobbers, opening the London Stock Exchange to foreign firms, and implementing electronic trading. These changes were not merely technical adjustments but represented a fundamental reorientation of British economic policy toward financialization centered on London.

Tony Blair and Gordon Brown engaged in conversation during the early 1990s, key figures in the rise of New Labour and London’s political-economic prominence

Crucially, Thatcher’s broader privatization program was designed by Nicholas Ridley through what became known as the Ridley Plan. This blueprint for privatization was explicitly intended to weaken trade unions and transfer economic power to financial markets—inevitably benefiting London-based institutions. The plan represented a conscious choice to prioritize capital over labor and financial services over manufacturing, with profound geographic implications.

As one analysis notes, Thatcher’s policies led to “an over-reliance upon one geographical region and a particular economic sector”. The government’s decision to embrace what it called “popular capitalism” was implemented through London-based financial institutions, further concentrating economic power in the capital.

New Labour’s Embrace: The City’s Capture of Progressive Politics

Perhaps the most significant political development in London’s rise to dominance was New Labour’s decision to embrace rather than challenge the Thatcher settlement. Under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, what became known as the “prawn cocktail offensive” saw Labour leaders systematically courting City of London interests. This represented a historic shift for a supposedly progressive party.

Gordon Brown’s approach as Chancellor was particularly crucial. He implemented what he termed “light-touch, risk-based” regulation specifically designed to benefit London’s financial sector. Brown explicitly argued for “not just a light touch but a limited touch” approach to financial regulation, declaring that “under a risk-based approach, there is no unjustifiable inspection, form-filling or requirement for information”.

The consequences were dramatic. Research shows that during New Labour’s tenure, “London’s share of the economic output has reached an all-time high,” increasing “more than 3 per cent since Labour’s election victory in 1997”. This was not accidental but the result of deliberate policy choices that prioritized London’s global competitiveness over regional balance.

Brown later admitted this approach was a “big mistake,” acknowledging that the regulatory framework he put in place “failed to address the ‘entanglements’ of different institutions and ‘how global things were'”. However, by then the damage was done—London’s dominance had been further entrenched through progressive political legitimation.

The Westminster Model: Political Centralization as Economic Strategy

London’s economic dominance is inseparable from its political centralization. The UK operates what scholars term the “Westminster model”—one of the most centralized systems among developed democracies. As the Mayor of London noted, “The UK is one of the most centralised countries in the world and London has limited control over the taxes raised in the capital”.

This centralization is not accidental but represents a deliberate constitutional arrangement. Research demonstrates that “the UK firmly remains one of the most centralised states in the OECD,” with England being “chronically over-centralised” and suffering from a “democratic deficit”. Local authorities outside London “face restrictions on their powers concerning welfare, education, and healthcare” and “lack substantial revenue-generating authority”.

Aerial view of London’s Houses of Parliament along the River Thames, symbolizing the city’s role as the UK’s political center

The Westminster system ensures that major economic and political decisions flow through London-based institutions. As one analysis explains, the “principle of indivisibility in the relationship between political and administrative elites” creates a “centripetal tendency in the British system, of power being drawn back to the centre”. This institutional design systematically favors London-based interests over regional alternatives.

The Rhetoric of Balance: Northern Powerhouse and False Promises

Even attempts to rebalance the UK economy have paradoxically strengthened London’s position. George Osborne’s “Northern Powerhouse” initiative, launched in 2014, promised to create “a northern ‘powerhouse’ of the British economy”. However, research reveals this was largely rhetorical.

During the supposed “Northern Powerhouse” period, London’s share of UK GDP continued to grow from 21.2% in 2014 to 21.5% by 2016. Analysis shows that “the North accounted for 21.3 percent of the UK’s deals” in 2013, but this fell to “17.3 percent” during the Northern Powerhouse period. Meanwhile, “London takes an ever-larger share of investment” despite the rhetorical commitment to rebalancing.

George Osborne in formal attire, associated with the Northern Powerhouse initiative and economic policy discussions in the UK

Osborne explicitly acknowledged this contradiction, stating that rebalancing should not come “at the expense of a ‘diminished’ London” and that “we achieve that not by pulling down our capital city”. This reveals the fundamental constraint on any rebalancing effort—the political class remains committed to London’s dominance.

Contemporary Consequences: Democracy, Inequality, and National Dysfunction

The cumulative effect of these deliberate policy choices has created what experts describe as a “London bubble” that distorts British democracy. Research demonstrates that “London’s distinctiveness from the rest of the UK” has grown dramatically, creating a situation where “the gap between the UK and its capital city has grown and grown”.

The economic data is stark. London’s GVA per employee is “39 per cent higher than the national average,” while the capital produces more than ever before in its recorded history. This concentration has created what the Resolution Foundation describes as “low growth and high inequality,” with typical British households now “9% poorer than their French counterparts”.

London’s political dominance extends beyond economics. As one analysis notes, when non-Londoners think of the capital, “it is the capital’s role as the home of the UK’s central government that springs to mind first”. This creates a situation where “‘London’ is often a codeword for dissatisfaction with government”.

The infrastructure investment pattern reflects these political priorities. Victorian-era infrastructure continues to serve London while being replaced with “cutting-edge digital signalling technology” worth over £1 billion. Meanwhile, Northern England continues to rely on infrastructure that is literally from the Victorian era.

Migration and Demographic Engineering

London’s dominance has been reinforced through demographic changes driven by deliberate policy choices. Research shows that migration “is delivering benefits in London,” with “each migrant worker contributes a net additional £46,000 in Gross Value Added (GVA) per annum to London’s economy”. With “approximately 1.8 million migrant workers in London, their total contribution is around £83 billion – 22% of London’s GVA per annum”.

This is not coincidental but reflects immigration policies designed to benefit London’s economy. The research notes that “migration into London, especially inner London, is concentrated overwhelmingly on 20-24 year-olds”. These young migrants provide the skilled labor force that sustains London’s knowledge economy while contributing to property demand that benefits existing London property owners.

The broader demographic pattern reveals systematic advantages for London. While “substantially more UK people moved out of London than into it,” the “positive net inflow” of international migrants “is not sufficient to offset the net outflow” but provides a crucial boost to London’s economic dynamism.

The Financial Crisis: Socializing Losses, Privatizing Gains

The 2008 financial crisis represented perhaps the most dramatic example of how political decisions have systematically favored London over the rest of the UK. Gordon Brown’s government orchestrated “a bailout for failing banks, whose total value reached £1.162tn at its peak”. This was combined with “£375bn of cheap credit to the banks through the policy of quantitative easing”.

As one analysis noted, “No other sector of the UK economy had ever received such levels of support in peacetime”. The Brown government’s “strategic decision to privilege banking over all other sectors of the UK economy, and to subordinate its wider British modernisation agenda to the defence of the interests of the City of London” was made explicit during the crisis.

This represented a clear political choice. Rather than allowing market forces to operate—the supposed ideological foundation of the deregulated system—the government chose to socialize the losses of London-based financial institutions while allowing them to retain privatized gains. No equivalent support was provided to manufacturing regions devastated by deindustrialization.

Constitutional Arrangements: The City’s Unique Status

London’s dominance is also maintained through unique constitutional arrangements that would be considered corrupt in most democracies. The City of London Corporation operates as “a sui generis (unique) local authority” with powers that extend far beyond normal municipal governance. It manages billions of pounds through its “City’s Cash” fund, operates its own police force, and maintains exemptions from standard transparency requirements.

The Corporation’s role in promoting “London as a leading global city for international trade and finance” represents an institutionalized commitment to London’s global competitiveness. This creates a situation where a local authority with medieval privileges operates as a de facto lobby for London’s financial interests within the British state.

The Corporation’s unique voting system allows businesses to vote alongside residents, creating what amounts to corporate representation in local government. This arrangement, which would be considered undemocratic in most countries, ensures that financial sector interests are systematically represented in London’s governance.

Conclusion: The Deliberate Construction of Dominance

London’s extraordinary economic and political dominance represents the cumulative effect of deliberate choices made by key political figures over centuries, with particular acceleration from the 1980s onward. From William the Conqueror’s medieval charter through Thatcher’s Big Bang to New Labour’s light-touch regulation, political leaders have systematically chosen to prioritize London’s global competitiveness over national economic balance.

The data reveals the stark results: London now accounts for 21.9% of UK economic output, the highest level in recorded history. This dominance extends across finance, where London handles 43% of global foreign exchange trading, politics, where all major decisions flow through Westminster and Whitehall, and demographics, where young skilled workers are systematically drawn to the capital.

The key figures responsible include not just Conservative politicians like Thatcher, Lawson, and Ridley, but also Labour leaders like Blair, Brown, and Mandelson who chose to embrace rather than challenge the City’s dominance. Even supposed “rebalancing” efforts like Osborne’s Northern Powerhouse have served primarily to provide rhetorical cover for continued London-centric policies.

The result is a uniquely unbalanced state where one metropolitan region exercises unprecedented dominance over a developed democracy. As research demonstrates, “England is one of the most centralised countries in the developed world” with “chronic over-centralisation” that “suffers from a ‘democratic deficit'”. This is not an accident of geography or market forces but the deliberate construction of political and economic elites who have chosen to concentrate power in London at the expense of democratic balance and national prosperity.

The implications extend far beyond economics. London’s dominance has created what amounts to a “London bubble” that distorts British democracy, creating a situation where the capital appears increasingly remote from the rest of the country. For any future Sgt Grumpy investigation, the evidence is clear: London’s dominance represents not market success but political capture—the systematic subordination of national interests to the global ambitions of London-based elites.